by Ray Hemachandra, with Jessica Aguilar and Lennin Caro

— data updated as of February 9, 2025

(Pulse aquí para leer este artículo en español—Click here to read this article in Spanish.)

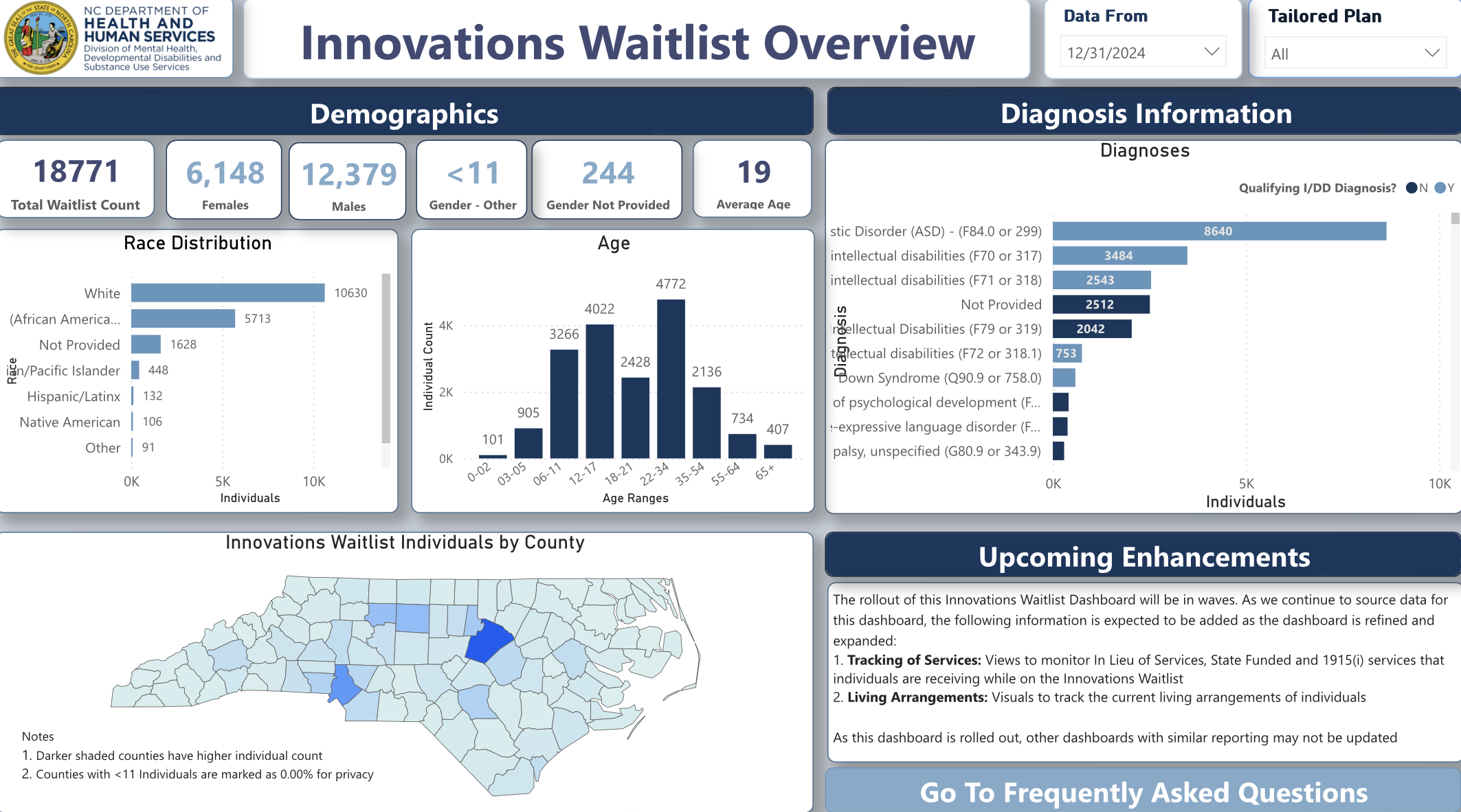

In North Carolina, the Innovations Waiver Waitlist Overview dashboard is a vital and commendable point of public-information access by the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services (N.C. DHHS) and the Division of Mental Health, Developmental Disability, and Substance Use Services. It was published in 2024 and is updated intermittently.

There are many takeaways when looking at the dashboard. Most obviously and urgently, of course, there are 18,771 people with significant intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) waiting to receive Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) from the primary program designed to keep North Carolinians in their homes and communities instead of in institutions.

That’s thousands more intellectually disabled adults and children waiting for Innovations Waiver services in North Carolina than receiving them. Some people receive limited alternative services. You can read more about the true awfulness of the waitlists for services in North Carolina and nationally here, here, and here.

That’s the biggest-picture concern, and it’s crucial. This massive, cruel, ongoing and still-growing failure—by government, first, and also by IDD advocates in our advocacy priorities—urgently demands a bold and passionate new commitment and deep investment for correction.

The next big, urgent thing the Innovations Waitlist Overview dashboard brings into the light is the massive and openly discriminatory underrepresentation and exclusion of intellectually and developmentally disabled Hispanic and Latino children and adults from the North Carolina system.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 11.4 percent of North Carolinians are Hispanic or Latino. That percentage continues to rise. (See https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/NC, currently with data from July 2024.)

According to the state’s Innovations dashboard, of the 18,771 people with IDD waiting for services, 132 are Latino or Hispanic.

If intellectual and developmental disability is distributed evenly between ethnic and racial populations, there should be 2,140 Hispanic or Latino people on a waitlist of 18,771 North Carolinians. There are 132. Rather than making up something reasonably in the neighborhood of 11 or 12 percent of the waitlist, Hispanics and Latinos make up 0.7 percent of it.

This deficit is a serious indictment of the way our system is and isn’t working, and it is in urgent need of correction. Let’s correct it together, and take important first steps now, even as we figure out with the Hispanic, Latino, and IDD communities what needs to follow.

First, let’s agree that the data is likely inaccurate. This data from the remaining four N.C. Managed Care Organizations (MCOs)—that have merged with other MCOs—may have been collected in different and to some extent unknowable ways. Also, racial and ethnic classifications have changed. So, for example, some people listed as White may be Hispanic or Latino, and some Hispanic or Latino people may be included under Not Provided and Other categories. As presented, multi-ethnic and multi-racial people are not defined or openly represented in the data, nor does the data clearly reflect and present how people self-identify.

Given the extent of the waitlist deficit for Hispanic and Latino children and adults with IDD, inadequate demographic data is only part of the picture. Still, one of our points of advocacy must be the government collecting better—more complete and more accurate—demographic data for every child or adult who is currently on or is being added to the Innovations Waiver waitlist, as well as for every person receiving services, with a reasonably swift deadline for doing so and with more trustworthy demographic data being presented publicly, including on the dashboard.

That’s necessary but won’t change the underlying issues that deter and prevent Hispanic and Latino children and adults with IDD from connecting to the service system and from receiving services. Waiting for more accurate data would only postpone correcting the profound deficits and meeting the needs.

So, substantive advocacy and recommendations need to address:

- diagnostic, system, and service competency and biases

- language barriers and needs, including reciprocal interpretation, translation, and accessibility

- community mistrust of government and some healthcare institutions

- cultural impediments to understanding and seeking support for developmental disabilities

We are describing significant challenges, and we are not going to pretend to have all the answers. Those answers and strategies need to be informed by and led by diverse, broadly representative Hispanic and Latino North Carolinians, including people with IDD and their family members, alongside leadership and staff at N.C. DHHS, in Managed Care Organizations, and in provider agencies and IDD engagement and advocacy organizations, including both state and local CFACs (Consumer and Family Advisory Councils) and the North Carolina Council on Developmental Disabilities.

A taskforce with a clear mandate should be created, certainly, and in short order.

Recognizing Gaps, Needs, and Discrimination

Jessica Aguilar is co-founder and director of Grupo Poder y Esperanza (the Group of Power and Hope), a member of the N.C. State CFAC, and the mother of twins with IDD and mental-health needs. Jessica describes both cultural and systemic obstacles to diagnosis and to service access.

“In many Latino countries of origin, people don’t know about autism, for example, or other diagnoses that don’t necessarily present physically,” she says. “So, except for Down syndrome, whether we’re talking about first- or second-generation Latinos here or about responses from older family members and the community, it’s hard to recognize or understand even the need to seek a diagnosis to get help and support.”

After receiving a diagnosis, complications continue. “Even with a diagnosis, Latino people say, ‘I’m scared to try to access services,’” Jessica says. “And if they do, they face constant discouragement and obstacles. For Spanish-language speakers, most of the informational materials and call centers are English-language-based. There are inaccurate translations of materials not designed for Latinos, and there aren’t nearly enough interpreters—even when they’re offered, the waits can be extreme and then they just cut you off a lot of times. The system becomes impossible to navigate or even to understand for people who have to take care of their family and work a lot just to get by.”

There also are significant challenges for Hispanic and Latino children, adults, and families receiving services. “For Spanish-speaking family members, in order to ask questions or to explain things, they need professionals who can understand and communicate with them,” Jessica says. “People can’t just use Google Translate—that doesn’t work well and causes everyone frustration until people just give up. We need to recruit more Spanish-speaking care managers and direct support workers. Often care managers don’t actually do their required check-ins with Latino families, and often the family member doesn’t get the services they need. Often they’re treated badly and with disregard.

“A worker or therapist will just stay on their phone the whole time that they are supposed to be working with someone. It’s fraud, and it’s discrimination. But mostly Latinos are not going to report it. They’re scared, or they don’t know how to.”

Lennin Caro is the Director of Camino Research Institute in Charlotte. Lennin describes a community stigma around mental-health care and services that may extend into and obstruct seeking support for family members with IDD.

“Statewide results of Camino’s N.C. Latino Community Strengths and Needs Assessment shows that 43 percent of 3,397 survey respondents say that no one in their household has any difficulties with any mental-health-related symptom,” Lennin says. “Only 28 percent of respondents say that someone in their household has ever used a mental-health service like counseling or therapy.”

Another barrier Lennin describes is the mistrust that many Hispanic and Latino people have about governmental and medical institutions, in particular noting what he calls the “chilling effect” of public charge—immigrants being denied status because they utilize government resources or benefits.

“The Latino Community Strengths and Needs Assessment shows that only 36 percent of Hispanics believe that the North Carolina state government supports Latinos,” he says. “There may be suspicion among Latino immigrants to engage with government-related services. This can be due to a combination of factors including inconsistent and unclear immigration policies like public charge, language barriers that make system navigation more opaque, and financial barriers related to cost and lack of insurance coverage.”

“Even if a child is U.S.-born, undocumented parents may be afraid to enroll their child in any service, including IDD-related ones,” Lennin says, describing how this community fear leads to families not accessing needed services—including ones they are eligible for—to stay safe. That then informs community expectations and norms around seeking help at all.

Taking Action and Engaging Solutions

Clearly, there is a lot of work to be done across IDD, healthcare, and governmental systems to recognize and then correct these profound obstacles and challenges—and to better support the Hispanic and Latino community in accessing support and care for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Here are some first, significant steps for North Carolina and N.C. DHHS to take that will be beneficial—and, likely, necessary—if we are to support and serve Hispanic and Latino children and adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities properly. At least some of the solutions for IDD can be extended into work being done for traumatic brain injury, mental health, and substance use recovery, as well—all areas that are positioned in North Carolina in the same division of DHHS: the Division of Mental Health, Developmental Disability, and Substance Use Services.

We recommend that the state:

♦→ Create a central outreach phone bank, chat, and website platform for the state specific to Hispanic and Latino people with IDD and their families, with a comprehensive resource bank and bilingual and culturally literate staff who can serve as point persons—essentially as connectors, representatives, and ombudspersons—with the four MCOs, with state government, and even with systems, organizations, and agencies of diagnosis, care, and services.

Staff for this comprehensive resource bank can connect people to resources and assist and walk people through the steps of getting on the waitlist, in accessing services, in receiving care, and in overcoming obstacles as well as filing complaints and appeals. They also can facilitate Latino and Hispanic people’s participation in public advisory, feedback, and advocacy opportunities.

♦→ Design and implement a large, ongoing, and Hispanic- and Latino-specific IDD education and outreach campaign encompassing awareness, acceptance, and diagnostic and service access for people with autism, intellectual disability, and other developmental disabilities and their families, as well as supporting Hispanic and Latino community education about IDD more broadly.

The campaign should be in both English and Spanish statewide and particularly target areas of the state with larger Hispanic and Latino populations. It should operate through relevant and appropriate online, social (including WhatsApp), print, and other marketing channels and platforms.

Awareness and acceptance materials should engage social and cultural expectations and norms. Diagnostic and service-access materials can point to contact information for the comprehensive resource bank.

We can measure response to and engagement with different campaigns—and then do more of what works.

♦→ Have truly substantial incentives for recruiting people who are bilingual and culturally literate as care managers and direct support workers, as well as for other roles across the system—including in leadership—especially reflecting local and regional populations.

♦→ Equip community health workers—promotoras de salud—with better information about intellectual disability, developmental disabilities, and accessing services. Significant investment in training, compensation, and recruitment that reflects the population, with a mix of bilingual U.S.-born and immigrant Latinos, will help alleviate mistrust and areas of misinformation about engaging the service system. Community health workers can also be trained to use the comprehensive resource bank as a support and a partner.

♦→ Require that *all* N.C. Division of Mental Health, Developmental Disability, and Substance Use Services, MCO, and state, regional, and local CFAC meetings, materials, and presentations include reciprocal interpretation (for spoken communication), translation (for written communication), and bilingual mechanisms for contribution and feedback.

♦→ Recognize that accessible and actionable language and communication aren’t achieved just by interpretation or translation. All of these efforts need to be assessed by a skilled professional for accessibility and actionability—and then continually assessed again for their effectiveness.

♦→ Hire a point person—with staff—in a Departmental leadership position to oversee all this work and be responsible for its successful implementation.

And just to include them among the action bullets, these two from earlier in this piece:

♦→ Improve the quality and accuracy of demographic data collection and reporting for Hispanic and Latino North Carolinians with IDD on the waitlist and receiving services.

♦→ Create a taskforce centering Hispanic and Latino voices for advancing this work.

The need is great and the goal is clear. Latino and Hispanic children and adults with significant intellectual and developmental disabilities should not face a discriminatory system in North Carolina with discriminatory structures, practices, and outcomes.

Instead, intellectually and developmentally disabled Latino and Hispanic children and adults—and their families—should receive well-designed, appropriate, and accessible information, support, and services so they can live inclusive, healthy, and good-quality lives in our communities throughout North Carolina.

Deep thanks to Jessica Aguilar, co-founder and director of Grupo Poder y Esperanza and a member of the North Carolina State CFAC, and Lennin Caro, Director of Camino Research Institute, for their review of and contribution to this article.