Often I’m asked “What are you?”

Racial and ethnic identity inform so much in our culture. The question asked really is a question of identity. “What are you?” masks the underlying question, “Who are you?”

When I was young I was black. My father, Neal Hemachandra, was black. His mother, Leathe Wade Colvert, was black. Her mother, Martha Pleasant, came from Virginia and slave plantations. She was black.

I was black even as I carried an Asian Indian name and just as much ethnic heritage: my father’s father, Balatunga Hemachandra, emigrated from Sri Lanka. I was black even as I was Jewish: my blonde-haired, blue-eyed Jewish mother’s family were immigrants from eastern Europe, and much of their family died in the Holocaust.

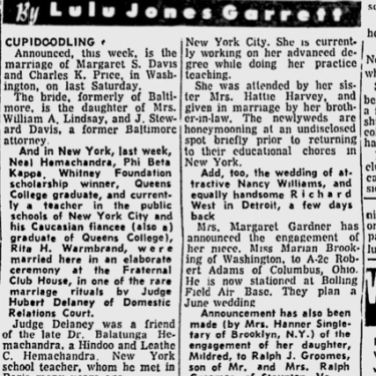

American history and family history confirmed this identity. One drop. My parent’s mixed marriage: they were married in New York City, where they both were born, by a prominent NYC African American judge, Hubert Delany, brother of the Delany sisters who became famous decades later. My parents’ marriage was reported in the black press in papers up and down the East Coast.

(Click on the circles for the full photos with captions.)

Racial definitions from the government, schools, and organizations reinforced my black identity. When my mixed-marriage parents moved into their then nearly all-white neighborhood, the neighborhood where I grew up on Long Island, they snuck in during the night. A petition was circulated to create a restrictive covenant.

I grew up with darker skin than my peers, the occasional racial epithet being hurled my way by other children, and a sense of otherness most accessible as blackness in the common culture.

It wasn’t even a question to me: I was black.

That is, I was black racially. In ethnicity, I was also Jewish: born to a Jewish mother, which is how Judaism transfers, and growing up in an area of New York where Jewish culture was well-represented.

That combination wasn’t a contradiction for me, even if it was for others. It was just who I was, and it made sense to me in terms of who my parents were, my most local of cultures.

Still, the racism in the area was endemic, as it was to the time. Non-specific to me, whenever there was a schoolyard fight children would gather around and rhythmically chant over and over again:

Fight, fight, dynamite,

Who’s the nigger?

Who’s the white?

I remember elementary-school teachers and principals breaking up fights, but never objecting to the chant or trying to stop it.

When I went to college and graduate school I participated in black organizations, including participating in CIC (Big Ten plus the University of Chicago, where I did graduate work) minority conferences at different schools and in a mentoring program. I never questioned my identity here; others never questioned it, either.

Still, my perception of how people saw me expanded: When I lived in D.C. attending Georgetown and then in Chicago, especially, out in the community people would frequently start speaking to me in different languages: Spanish, often—I really should have taken Spanish instead of French in high school and college—but also Greek or Italian or tongues unknown. Asian Indians, noting my surname, would often inquire if I was from India.

And as I moved away from cities—to Bellingham, Washington, for a dozen years and then in 2006 to Asheville, North Carolina, where race and blackness are seen through an entirely different regional and local prism that is still largely inaccessible to me as a concept or even a feeling—my identity of blackness became increasingly a claim of blackness that was sometimes received skeptically or critically.

I still had the “otherness” thing. It was just an undefined otherness.

In addition to the change of locations, which continues to be consequential, during the past decade the concepts and tags multiethnic, multiracial, and transracial have been increasingly introduced and become influential across the culture.

Multiracial didn’t exist on the checkbox forms when I was growing up or when I went to college, nor did it exist much as a functional idea. In the United States, anti-miscegenation laws weren’t even deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court until the Loving vs. Virginia decision in 1967, the year I was born; 16 states still enforced such laws until that unanimous court verdict. At best, melting pot meant living side by side, or at least in nearby neighborhoods, rather than intermarriage or interchildren.

But now the categories of multiethnic and multiracial, unknown when I was younger, are everywhere. I’m mostly glad for that change and for what it says about a progressing reality and, I hope over time, an increasingly generalized embrace of a more inclusive society—one that doesn’t diminish identity but also doesn’t use it to exclude, injure, and cause harm. I regard myself as black—I am black—even as society’s framework shifts.

I usually indicate that on these forms, but occasionally I do check the “multi” box. They are both true. It’s hard, because what you call me and how you think about me matters. I can check that “multiracial” box without questioning my blackness, but doing so likely takes away the legitimacy of my blackness to you, fraying and distorting the identity I’ve had across the entirety of my life and that I will always have. While not trivializing what’s possible now that wasn’t before, that loss is consequential.

The power of naming has been on my mind lately, as my son ages. Nicholas is 13 and autistic.

Here’s a change I’ve made:

Parents of autistic children and professionals overwhelmingly prefer what’s called person-first language: “My child has autism”; “She is a person with autism”; “There are more and more children with autism.” Autistic adults overwhelming choose what I’ve recently learned is called identity-first language: “He is an autistic man”; “I am autistic” or “My friend is autistic”; “Autistic adults form a growing population demanding not just acceptance but also respect.”

The former construction, a language long fought for by parents and some professionals, says my child is a person first, and autism is just one part of who he or she is or they are. It’s not the defining aspect of her, his, or their personhood.

The latter insists autism is essential to identity. Proponents of identity-first language say you would not call a black woman “a woman with blackness.” That doesn’t mean being black is the woman’s only quality, nor does it mean the adjective “black” is relevant to every discussion about the woman and always needs to be used, but being black nonetheless is a quality essential to her identity: so, too, with autism, autistics say.

I now use identity-first language because it seems to me a community should be able to name itself—autistics get to name autistics, regardless of the opinion of autism professionals or parents of autistics—and I have yet to meet an autistic adult who doesn’t prefer identity-first language (even as some are not overly concerned about it). You can read a fuller exploration of this issue by Lydia Brown of Autistic Hoya here or a short, seminal indictment of person-first language by Jim Sinclair here.

My son, Nicholas, has a lot of labels already. He is autistic. He has diagnoses of OCD and severe mixed expressive/receptive communication disorder. He is multiracial and multiethnic, with the diverse heritage from me I described and a Cree-Blackfoot mother, although it’s common for someone to check the “white” box for him without asking, with his relatively fair skin and the gray-blue eyes he shares with my late mother. And, of course, his most obvious labels are that he’s strikingly sweet, gentle, and loving.

All of which he’ll just have to accept as part of his identity.

Nicholas is autistic, prominently and essentially. Autism has shaped and guided who he is, how he engages the world and himself, his relationships, how he learns, where we live, how we spend our time, and how we structure our lives in so many ways. I would like him to be proud of his autistic identity, to embrace who he is and not to think of his autism as something to hide or to overcome.

I hope he’ll come to know that being autistic is a blessing that has enriched his life, as well as mine. If you take away the autism, you’d have a different child. I don’t want a different child. I hope he doesn’t want to be different in such an essential way, even as he gets to have his own life and his own emotions around that life.

And I wonder, too, if someday decades from now acceptance and understanding of the ideas of neurodiversity and a neurodivergent spectrum might become so common, and that a prescriptive goal of neurotypicality might become so outdated, that the term autistic as a population-cluster definition starts to outlive its usefulness and the autistic identity starts to fray.

We know the loss would be consequential even as we aspire toward that day.

If you enjoyed this article, please share a link to it on your social media channels to spread the word or leave a comment below. You might also like to read another very personal piece about race:

- Definition as Destiny: Breaking Autistic Boundaries

- Poppa, Do You Have Autism?

- Hammer and Screw: Autism Acceptance and Rejection

- Autism Adulthood: Caring for the Future and the Present Moment

- Autism 101: Hating Your Autistic Child

- Accept or Reject: Part one of a series on autism value contrasts

- Top 10 List: Things to Remember When Working with Autistic Children

- 7 Values to Live By: Autism Across Schools and Classrooms

- No “Because” but Love—Intellectual Disability, Identity, Representation, and Value

Thank you very much for your interest and engagement. I truly appreciate it.

As I read this I remembered all the times I’ve heard people using names to put others in boxes, and how angry I feel when this happens. Each of us is unique and no one really fits in a group box so why do we continue to define people by one of the groups of which they are a member? Are we not first fellow human beings and isn’t that what is really important?

LikeLike

Reblogged this on TAG: The Autism Gathering and commented:

We’re tagging Ray Hemachandra’s grace-filled writing today, as he looks at the role of identity and essence, the words we choose and those we’re given. The power of naming: who decides? Thank you, Ray, for sharing your words and your experience with us.

LikeLike

Thanks so much for sharing this, Ray — and for the link to my article. You might also want to read my recent article, “I, too, am racialized.” about my experiences as a Chinese transnational, transracial adoptee. (Also, always great to run into a fellow Hoya on the web. If you’re interested, I would love to connect more. My email is lydia@autistichoya.com.)

LikeLike

Thanks for your piece. Our family has come slowly to acknowledge Asperger symptoms & at first I was drawn to learn everything I could. Knowledge is power, right? But gradually I realized how unhelpful & distancing that was. My son & husband are dear loving people who have personality traits that can be labeled, which may be helpful for understanding & acceptance but not much else. They are not that. We are all on a spectrum, and the best times are when we can have a good laugh together in our differences. Our diversity is our strength although the world doesn’t make it easy. Peace be with you.

LikeLike

Ok, so a question. I am a direct care provider for people with autism and I have been using person-first language for years. This identity-first language makes sense to me on the face, but also raises some thoughts. I am a lesbian. My other lesbian and gay friends and I call each other and ourselves all sorts of “gay” names but I don’t necessarily think that I want a straight aquantinance calling me a lesbian or saying something like “that lesbian over there”. I would much prefer that the general community see me first as a person, and second as my sexual orientation. It seems similar in the african-american community…. I don’t say “that black person over there” when pointing someone out and try not to use “black” as the main identifier when describing someone. I understand that these are different examples, but they are all things that you are born as as opposed to a choice. So I guess my question is, how do we, as providers, family members, friends, etc. refer to people on the spectrum so that we are being respectful and seeing the person as a person while still respecting their personal identity and the fact that autism is not a disease or disorder or negative thing at all but simply something that makes a person unique like everything else about them (something I deeply believe and have since I began this work 7 years ago)? I hope this was clear enough that you aren’t completely confused :-) I would love to hear people’s perspective who are on the spectrum also!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Kristen, conceptually your empathetic, smart question will provoke reflection for me. But practically it doesn’t, because there’s a simple response: by my experience both with online virtual bloggers and with members of my real-life autism community, and from the leading groups of autistics themselves, adult autistics with a preference overwhelmingly prefer that people use identity-first language rather than person-first language. The community gets to name itself, not have what it’s called imposed from the outside — that is, imposed by autism parents, professionals, and organizations that, as a whole and a general rule, give dramatically little weight and even dismiss as irrelevant the experiences, perspectives, and expressed preferences of adult autistics. Also, yes, I don’t always call someone a black woman — I’ll sometimes call her a woman without modifiers or with other ones when they’re the ones that are relevant. So, too, with an autistic person, but when I do it will be using the language “autistic person,” not “person with autism,” out of respect for this community’s strong preference. And, finally, if an individual autistic expresses a different preference, I’ll respect that in my language used with her or him, as for example I’ve had women friends from the gay community who prefer lesbian or queer as the descriptor they use. ~ Ray

LikeLike

I appreciate your insight. Thank you, Ray!

LikeLiked by 1 person

thank you for this piece. my twins are also autistic, multi-racial, individual and awesome people. this resonates with me and i look forward to reading older/further insights.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really enjoyed this article. My sons with autism are at different places of awareness about having autism. My older son realizes he has it, but I have never heard him refer to himself or anyone else as autistic. Maybe he is still internalizing what it means to him. To be honest, I don’t know how to have that conversation. My younger son doesn’t know he has autism. He does think of himself as different. This isn’t always a positive. Thanks for the information.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on blonde2dye4 and commented:

Very interesting thoughts on what autistic people want to be called.

LikeLiked by 1 person